The story of an enigmatic woman across a state border

In July 2018, we set out across to the state of Rajasthan, miles away from Mumbai, the concrete jungle. After a three-hour road journey from the main city, we reached Bhap, a little-known village in Western Rajasthan. It is home to approximately 10,000 people of which only 4000 are women (Census, 2011).

We were here to undertake an assignment under the banner of ‘The Community Program’ (TCP) by the Market Research Society of India (MRSI).

The TCP is MR industry-funded program for young researchers to give back to the community by providing research and insights to not-for-profits that cannot typically afford it. [Other excellent case studies from TCP are Driving Change in Behaviour Management and Government Policies for the Disabled vs. Ground Reality].

The assignment was for Women Serve, a not-for-profit, operating out of Western Rajasthan, India. The NGO has been working towards advancing the status of women in six different villages specifically in the district of Paholdi.

The brief was simple – the organization was looking to establish a community park which would provide a safe place for women to improve the quality of their life and that of their family by learning various skills. This community park would also serve as a medium for women to exchange ideas and grow personally.

An answer to the key questions – Would a community park be welcomed by women and what would be the possible triggers and barriers to participate?– would then serve as a template for action for other villages where Women Serve would run the program.

When we got down to our ‘drawing board’, we realized that for Women Serve to make the right decisions about various interventions, it was essential for us to look at the woman in Bhap through a holistic lens.

This comprehensive lens was used throughout the designing and execution phases of the study. Thus, we broke up our research objectives into the following

- Identify the needs and motivations of women

- Identify their deep-rooted belief and aspirations

- Identify activities that she could engage in at the community park

Furthermore, our study was designed in the following way:

In our one week in the village, we did 30 qualitative interactions – a mix of group discussions as well as one on one interactions. We also gave shape to a quantitative questionnaire, right on the field – basis our learnings from the interactions – and performed 130 interviews representing all layers of the society in the village.

For e.g. several communities i.e. castes inhabit the village – a reality that became prominent once we were on the ground. It was critical for us to get a representative response – since one’s caste dictates the way of living in the village. For instance, the higher one is in the caste ladder, the more likely one is to receive education. These are dimensions could have been easily missed had we not spent the time with the villagers.

Due to our holistic and dynamic approach, we were able to observe nuances that otherwise one would possibly skip on. For example, all our qualitative interactions happened at the woman’s house – giving us the opportunity to observe her home life and her interaction with her family members. For instance, we were able to pick up on her hesitation to admit her TV viewing patterns in front of her in-laws and husband.

We also met with influencers in the village – the head of the village (Sarpanch) as well as the hostel warden to understand the workings of the village from a third person’s perspective.

Our study provided us with key insights that gave the organization some new directions and helped make some reiterations on directions they wanted to take.

It is important to note that the stakeholders of the NGO live in big cities and the key sponsor is in USA. Our research brought to life the context that otherwise would have been difficult for the NGO.

The Bhap woman since her birth is a burden to her family. Thus, being married off in her childhood – sometimes even at birth. Education is out of the question. Her life is spent catering to the needs of her family, within the four walls.

Given this social context, she lacked the self-confidence to even step out of the house, much less dream. Dreams and aspirations are words that did not seem to belong in their dictionary.

In her complex reality, her only solace is engaging in the activity of sewing. The activity is so deep rooted in her life that one can find evidence of it when one visits homes in Bhap – you will often find them displaying their work to visitors.

The impact of the activity was one of our key learnings from the study. Along with cultural rootedness, it also allowed her to work from the comfort of her own home. Moreover, most women saw it as a possible source of income. One of them said to us, “My neighbor is uneducated like me. But she knows stitching so she earns 3000 a month”. Thus, this was an avenue for her to increase her confidence and help her stand on her own two feet (financial independence) in the truest sense.

Moreover, through our quantitative learnings, we found that this activity as part of the community park was highly endorsed by women for the above reasons and more – it was an activity that was acceptable in the community and no one would raise any questions if she left her house to pursue and excel at this activity.

Knowledge sharing sessions as part of the community park was another action step for the organization. After a day’s work women are often seen visiting each other. This opportunity could be utilized to share stories and learn new skills.

Thus, the study provided key nudges that would push the boundaries slowly and steadily for the women of Bhap and go a long way in making sure that Women Serve is able to make dreams and aspirations a reality for the coming generation.

About the Authors: Niyati Taggarsi, Research Executive, Ormax Consultants, India

(The study was done in collaboration with Madhur Mohan, Research Manager – Kantar)

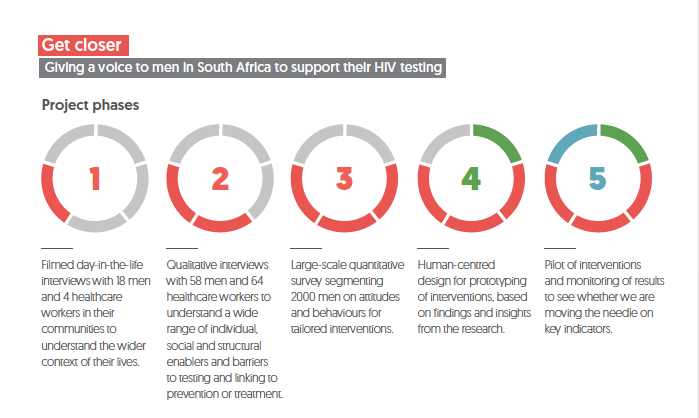

In South Africa, adolescent girls and young women make up around 2/3rds of new HIV infections yet men account for slightly more than half of AIDS deaths.

In South Africa, adolescent girls and young women make up around 2/3rds of new HIV infections yet men account for slightly more than half of AIDS deaths.